Shifting Gazes | Leah Band

Whose story is the landscape? Is it mine, is it yours, is it ours? Is it the landowners or the private corporations? Or is it a story more ancient, feminine, and fantastic?

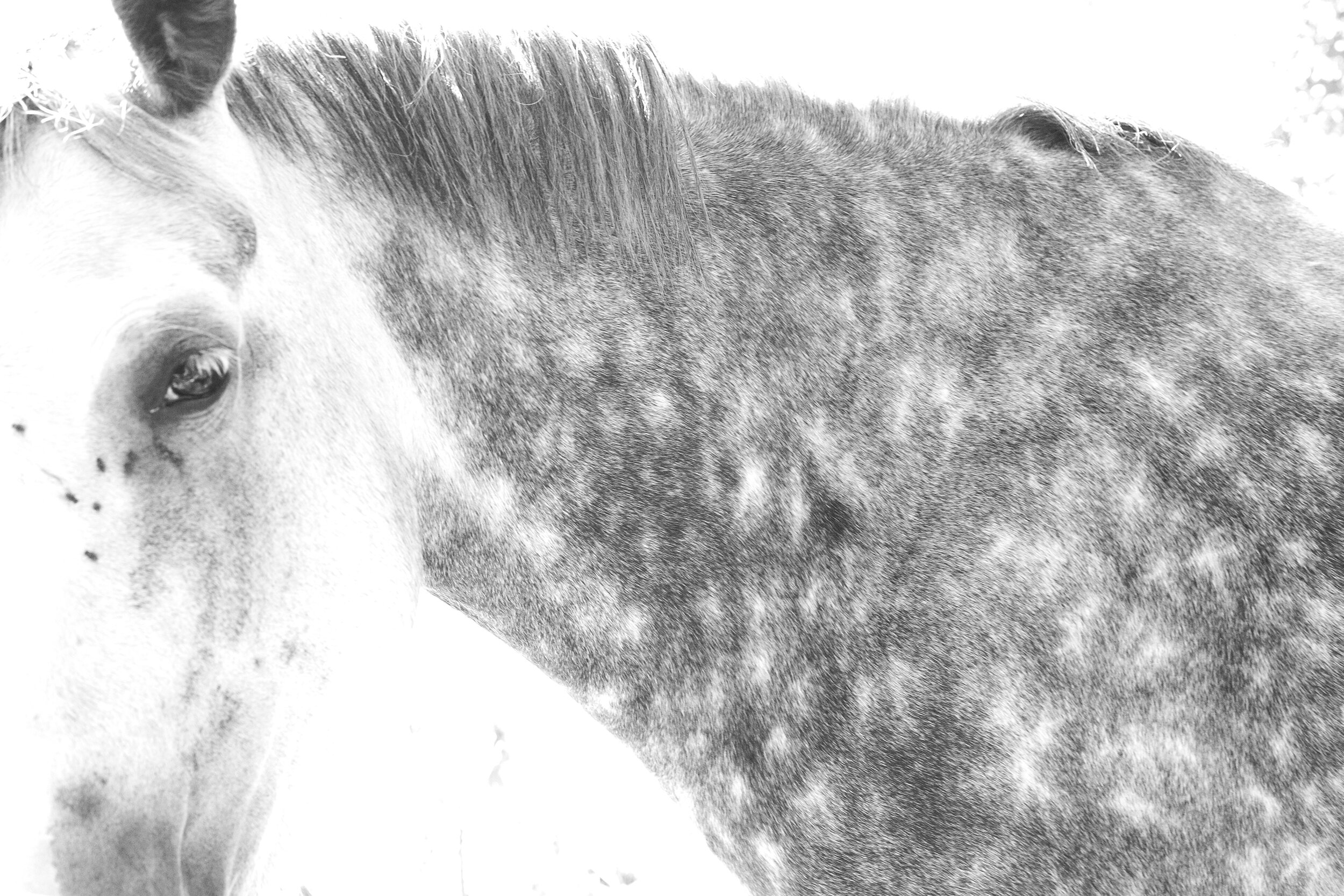

Throughout the past year I have spent time making images in the landscape which surrounds me—a familiar, gently rolling agricultural terrain located neatly in the centre of England. Starting autobiographically and working intuitively in black and white I have used the camera, alongside writing, as a thinking tool to explore my reconnection to this place, where I grew up, while actively considering our relationship more broadly, culturally, and politically to landscape. Who has access to natural spaces, whose bodies are welcome in the landscape, and how through attentive ways of being and slower ways of looking we might shift the gaze and free ourselves from exclusion?

The lockdown has in many ways heightened our awareness of our surroundings. We have learnt, or been reminded, how spending time in nature—seeing a mountain, walking through a bluebell wood, or listening to the waves roll in—brings us innumerable physiological and psychological health benefits. When birds sing, we feel safe, when we see fractals—repeated patterns found in nature, for example in the shape of fern leaves, snowflakes, and the branches of trees—brain waves are provoked which lead us to relax. Walking in woodland has been scientifically proven to reduce stress and boost our immune systems. And yet, our disconnect to the natural world is stark with huge social inequalities in levels of access to quality green spaces. In England, where 83% of the population live in urban areas, we have a right to access just 8% of the land and 3% of the waterways, meaning these pockets of green spaces often have a cost to travel to and are out of reach to many. Which begs the question, how can we benefit from, value, nurture, and love what we don’t ‘know’?

Landscape as a genre has historically privileged the white male perspective—the commanding viewpoint of ownership and domination. ‘For the aristocracy, landed gentry, and nineteenth-century industrialists, land ownership symbolised hereditary status or entrepreneurial success. As John Berger argued, landscape paintings operated to reassure this status.’ (Wells, 2004) From the seventeenth-century Dutch paintings of windmills, ships, and burgher estates in the landscape celebrating mercantile success to Capability Brown and the nineteenth-century English landscape garden to the twentieth-century American western ‘wilderness’ of Ansel Adams, portrayals of the landscape have benefited a particular way of seeing, being, and experiencing the landscape.

Whilst making my work I have sought to question traditions of Landscape as a genre and set of photographic practices—preferring to zoom in rather than zoom out, to create less traditional, more messy, sensual, and feeling based images and a slower and more attentive way of looking and being in the landscape. Within my research I am inspired by female and non-binary artists who engage critically with the landscape, picturing the environment, and making their own maps of experience to reclaim the landscape and in the process freeing ourselves from one kind of burdened seeing. Artists who continue to inspire me include Odette England—who manipulates, tears, folds, and physically disrupts her landscape imagery, Sadé Mica—who works with their body in the landscape and Whitney Hubbs to name a few.

The landscape shapes and is shaped by the histories we learn, informing the systems and structures we live by, it is a socially constructed space. Through attentive ways of being and slower acts of noticing I consider the potential to alter these traditions and imagine new ones. Now’s the time to free ourselves and the landscape.

by Leah Band

All images shown are the artist’s work.

Leah Band is a photographer from the UK with 15 years of experience working professionally in commercial and fashion photography. She has recently completed her MA Photojournalism & Documentary Photography (LCC) and is currently developing her personal practice. Her work explores themes of landscape, politics, power, and autobiography reflecting upon personal narratives through a feminist lens.

I am reading:

Fehily, C., Newton, K. and Wells, L., 2000. Shifting Horizons. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd.

Hayes, N., 2020. The Book of Trespass: Crossing the Lines that Divide Us. 1st ed. London: Bloomsbury

Jones, L., 2020. Losing Eden. 1st ed. [S.l.]: Penguin Books

Kelly, P., 1994. Thinking Green! 1st ed. Berkley: Parallax Press

Monbiot, G., 2020. The trespass trap: this new law could make us strangers in our own land. [online] the Guardian

Tree, I., 2018. Wilding. 1st ed. London: Picador

Wells, L., 2004. Liz Wells (Hg.): Photography. A Critical Introduction. 3rd ed. Oxford: Routledge, p.290.

Wells, L., 1995. Viewfindings. Tiverton, Devon: Available Light

Suggested sites:

https://www.righttoroam.org.uk/

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n4_DxRne3Yc